Subject title: Rights and Freedoms

Are you interested in: the fight for justice and equality for Indigenous Australians?

What we do: You will learn about the people who fought against discrimination and injustice for the rights and freedoms of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This will be done through a number of case studies of key turning points in Australian history. From the resistance to the missions and reserves, to campaigns for equal rights, land justice, self-determination and constitutional recognition. You will learn about the people and the historical conditions that acted both as barriers and enablers for change.

What we learn (skills knowledge and understandings): You will come away from this course with an understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders peoples’ historical perspectives and how this both fits with and clashes against mainstream narratives of Australian history. You will be able to identify the way in which historical sources are used to shape interpretations of history from different groups and use them to form your own arguments.

What you will be assessed on: A historical source analysis, an analysis essay & a multimodal campaign.

1838: Myall Creek massacre, New South Wales

Australian Aborigines Slaughtered by Convicts by Phiz

Early in the morning of 18 December 1838, seven men were publicly hanged at the Sydney Gaol. They were the first British subjects to be executed for massacring Aboriginal people.

The Myall Creek massacre was neither the first nor last massacre of Aboriginal people in Australia but the NSW Supreme Court trials that followed set a judicial precedent. However, attitudes towards such massacres took longer to change.

Gamilaraay elder, Uncle Lyall Munro, 2013:

[The Myall Creek massacre Supreme court trials were] the first place white man’s justice done some good. Right across Australia, there were massacres. What makes Myall Creek real is that people were hanged, see. That was the difference.

By the 1830s, frontier violence around NSW had become so widespread that the murder of Aboriginal people by British colonial stockmen, settlers and convicts was generally accepted, despite British law clearly articulating that it was a crime punishable by death.

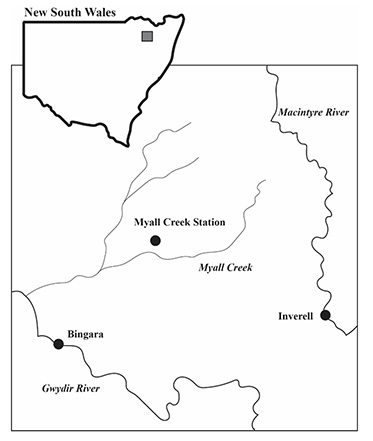

The massacre at Myall Creek was just one of a sequence of violent events that accompanied settler expansion in the Gwydir region of north-eastern NSW in the 19th century.

While it is likely that only a fraction of the violence is recorded in the conventional historical record, it is telling that a contemporary authority and eyewitness, Muswellbrook police magistrate Edward Denny Day, termed this conflict ‘a war of extermination’.

Violent attacks increased in savagery towards the latter part of the decade. The summer of 1837–38 was particularly violent.

Major James Nunn, the Commandant of the New South Wales Mounted Police, had been sent from Sydney to lead a punitive expedition against the Aboriginal people who had killed stockmen in separate incidents of Frontier conflict.

His response, however, was extreme. On 26 January 1838 Nunn and his men massacred up to 50 Aboriginal people camped at Waterloo Creek. They also encouraged nearby stockmen and settlers to murder any Aboriginal person they came across.

By the mid-1830s conflict had greatly reduced the population of the Wirrayaraay people, a tribal clan of the Gamilaraay nation.

Seeking sanctuary, a group of Wirrayaraay people decided to camp on Henry Dangar’s property at Myall Creek station near present-day Bingara, in May 1838.

A mutually beneficial arrangement evolved whereby the Wirrayaraay people had temporary reprieve from violence while their men assisted various stockmen with their work on nearby stations.

While the Wirrayaraay people were camped on Dangar’s property, the station hands, and particularly the assigned convict stockman Charles Kilmeister, enjoyed friendly relations with them.

The stockmen and the Wirrayaraay people spent time together in the evenings dancing and singing by the campfire. Some of the names that the stockmen gave the Wirrayaraay people have survived in the court depositions: Old Joey, King Sandy, Sandy, Martha, Charley, Heppita, Tommy, and Daddy.

Just before sunset on 10 June 1838, while the Wirrayaraay people were preparing for their evening meal, a group of convicts, former convicts and one settler arrived at the station fully armed. The group tied up the frightened Wirrayaraay people and led them away from their campsite.

Two women and a young girl were set aside, while another young girl was given to Yintiyantin, an Aboriginal stockman whose country was further south and who worked on the Myall Creek station. Two boys escaped by jumping into the creek.

George Anderson, hut keeper at Myall Creek station, later described the terror of the Wirrayaraay people as they were led away and slaughtered. Afterwards, their bodies were piled up and burned. The remains of at least 28 corpses were later observed at the site, but the final death toll has never been confirmed.

Myall Creek Massacre by Vincent Serico

Conspiracies of silence usually shrouded massacres of Aboriginal people and perpetrators were rarely punished.

The Supreme Court trials that followed the Myall Creek massacre were therefore exceptional, firstly because of the final outcome (the execution of British subjects), and secondly because of the wealth of information that the court transcripts preserved detailing the events leading up to the massacre and the legal proceedings.

The process of justice was initiated by three individuals who reported the event: station manager William Hobbs, local police superintendent Thomas Foster, and settler Frederick Foot. It was carried out by the new governor Sir George Gipps and the Attorney-General John Plunkett.

Gipps instructed the Muswellbrook police magistrate Edward Denny Day to investigate. On visiting the site and discovering partially burned bone fragments, Day took depositions from 19 witnesses.

These depositions provided the grounds on which Day arrested 11 of the 12 perpetrators and transferred them to the Sydney Gaol for trial. The only free settler among the perpetrators, Hawkesbury-born John Fleming, fled and evaded capture.

The memorial stone at Myall Creek

Participants walking to the Myall Memorial site in June 2015

On 15 November 1838 the first trial was held in the NSW Supreme Court before Chief Justice Sir James Dowling and a jury of 12 settlers. The first trial set out to establish that murder had been committed at Myall Creek and that the accused were guilty of this crime.

The prosecution centred around the burned skeletal remains of a very tall Wirrayaraay adult male, identified as ‘Daddy’.

The so-called ‘Black Association’, a group of landowners including Dangar, funded a formidable defence team to represent the accused on trial. The ‘Black Association’ allegedly set out on a program of intimidation and advised jurors to absent themselves from court.

At the conclusion of the trial, none of the witnesses, such as the Myall Creek hut keeper George Anderson, could swear that the remains of the large body was that of the Wirrayaraay Elder, Daddy. Therefore, despite the damning evidence presented, the jury declared all 11 defendants to be not guilty after less than 20 minutes’ deliberation.

However, Attorney-General Plunkett declared dissatisfaction with the verdict and kept the prisoners in gaol pending trial on new charges and using different evidence, this time indicting the prisoners for the murder of a Wirrayaraay child.

The defendants’ counsel had advised his clients to remain silent during the trial, but Plunkett hoped that they would give evidence against each other when divided and so separated them into one group of seven and another of four.

Given the high level of negative attention that the first trial received in the press, it became increasingly difficult to assemble a jury that would turn up to court let alone remain impartial.

Indeed, ferocious arguments were taking place throughout the colony as to whether a fair trial could be held at all. On 26 November the trial was postponed to allow the defendants’ counsel to read the new charges, and the following day legal arguments took place as to whether the defendants could be retried.

The second trial officially began on 29 November, yet a large number of men who had been called for jury service failed to turn up. Plunkett asked the judge to fine them harshly. Penalties of up to £10 were issued.

The lack of sufficient jurors led the Court Sheriff to ‘pray a tales’, which meant hauling in any male passer-by in the vicinity of the court. Once a full jury was present, the trial began.

Seven of the defendants were tried by a new judge, William Burton. At the conclusion of the second trial, all of the seven men were found guilty and sentenced to public execution.

Although the four remaining defendants (John Blake, James Lamb, George Palliser and Charles Toulouse) were to be prosecuted at a trial in which Yintayintin would give eyewitness testimony, this never took place – Yintayintin disappeared under mysterious circumstances and the four surviving perpetrators walked free in February 1839.

A British settler, JH Bannatyne, wrote to a friend in England and described the trials, relating how they had ‘created an extraordinary sensation in the Colony and will be the subject of gossip for many a long day yet’.

The colonial community of New South Wales was more outraged by the execution of British citizens than they were by the massacre of the Wirrayaraay people.

The fate of the escaped settler, John Henry Fleming, reveals much about the culture and society of the colony of New South Wales at this time. The obituary of Fleming published in the Windsor and Richmond Gazette in 1894 testifies to the long and rich life that he enjoyed after the massacre.

The privileged status that settlers enjoyed in the colony at this time enabled Fleming to escape, hide and reintegrate into society, despite the atrocities for which he was responsible being so well known and there being a lucrative reward for his capture.

In contrast, William Hobbs, one of the three men who reported the massacre, lost his position with Dangar and had great difficulty finding subsequent employment.

John Blake, one of the four perpetrators who escaped conviction, committed suicide in 1852. It has since been speculated that this reflected the trauma and guilt arising from his involvement in the massacre.

The executions of British subjects for the murder of the Wirrayaraay people hardened colonial attitudes towards the First Peoples of Australia and shaped later behaviours on the Frontier.

In Australian English, the word ‘dispersal’ became the commonplace euphemism used to refer to the killing and massacre of Aboriginal peoples, which went on to take more insidious and devious forms: disease, starvation and the poisoning of food rations are just some of the ways that the Indigenous population was further decimated.

Meanwhile, perpetrators took better steps to cover their tracks and avoid prosecution.

While today it is acknowledged that the First Peoples of Australia have deep connections to their country, the often brutal ways in which they were dispossessed of their homelands during colonisation are not.

One of the most powerful and pervading legacies of 19th- and early 20th-century colonialism in Australia has been the failure to discuss how the British colony was established through Frontier conflict such as the Myall Creek massacre.

The Myall Creek memorial site, which opened in June 2000, is important because it explicitly commemorates a massacre that is an example of this otherwise unspoken conflict.

In this way, the memorial site stands as both a site-specific and a national monument, in that it preserves memory of one particular massacre but is also representative of many more that took place across the country.

The memorial site is also important because it has been set up by Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in acknowledgement of our difficult, shared history.

Every year on the Sunday of the June long weekend, hundreds of people, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, gather at the site to attend an annual memorial service.

Descendants of the victims and survivors, such as Aunty Sue Blacklock, Aunty Elizabeth Connors and Uncle Lyall Munro, as well as descendants of the perpetrators of the massacre, such as Beulah Adams and Des Blake, come together to remember and reflect on past atrocities, as well as to express shared aims for the future.

Gamilaraay elder Sue Blacklock, one of the founders of the memorial site and service, talked about what the annual service and the reconciliation process means to her in a 2013 SBS interview:

It has lifted a burden off my heart and off of my shoulders to know that we can come together in unity, come together and talk in reconciliation to one another and show that it can work, that we can live together and that we can forgive. And it really just makes me feel light. I have found I have no more heaviness on my soul.

Documentary, History

The history of Australia from an Indigenous peoples' perspective, beginning with the 1788 arrival of the First Fleet in Sydney and ending in 1993 with Eddie Kolki Mabo's legal challenge.

Start Here

1h 10m

The 1788 arrival of the First Fleet in Sydney results in cautious friendships being formed between the First Australians and the British Empire. Yet within three years, relations sour as settlers spread out across the land.

Ever since the Aboriginal flag was first flown publicly in Adelaide’s Victoria Square in 1971, the Aboriginal flag has become arguably the most powerful symbol of resistance within the ongoing fight for land rights and basic human rights. The flag has been at the centre of protests and other monumental occasions in recent history. To this day the Aboriginal flag provokes both pride and tension within Australian society. You might be surprised to learn this didn’t happen by accident, but rather by design and perfect timing.

The flag was designed in 1971 by Harold Thomas, a Luritja man from central Australia, who at the time had recently graduated with honours from the South Australian School of Art in 1969. Thomas felt the need for a flag after attending the National Aborigines Day march in 1970 where the Union Jack was flying front and centre. Over the next few months while working at the Museum of South Australia, Thomas came up with a number of designs but finally (with the help of Gary Foley) chose the current Aboriginal flag.

What do the colours of the Aboriginal flag mean? What do the colours of the Aboriginal flag represent? Those are some of the first questions asked by people learning about Aboriginal culture. There are only three colours; red, yellow and black. The flag consists of a red rectangle which sits below a black rectangle with a yellow circle in the middle.

Red – The red symbolises the land we walk on and red ochre.

Yellow – The yellow represents the sun which gives us life.

Black – The black represents our people. The fact that we walk on the land was another reason why Thomas felt it was appropriate to put black above the red for his design. Thomas also felt it was essential to incorporate black into the flag after witnessing the power the black consciousness movement was having in America. Thomas has stated that all three colours (in ochre form) were consistently prominent among the Indigenous artworks he handled at the South Australian Museum.

The Aboriginal flag was first flown on the 12th of July 1971 in Adelaide as part of National Aborigines Day. After witnessing the symbolic power the flag had on both Aboriginal and non Aboriginal people, land rights activist Gary Foley took the Aboriginal flag to Sydney where he campaigned for the flag to be adopted in Redfern by the Black Caucus. According to Foley, he is not sure if he took the first original Aboriginal flag from Adelaide. The flag that he took eventually reached Canberra but the whereabouts of these flags still remain a mystery.

Spreading the news of the Aboriginal flag to all Aboriginal communities in the early 1970’s would have been next to impossible. But In 1972 a political and media storm was brewing after the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was established on January 26th. The establishment of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy made national and international headlines. The embassy also drew in Aboriginal activists from as far away as Arnhem land. By July of 1972, the Aboriginal flag was flying at the embassy and was later selected as the official flag of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy.

During 1972, the members and supporters of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy were also subjected to brutal treatment from authorities. This brutality actually helped to build a connection to the flag for Aboriginal people who heard the news in other regions. The Embassy was campaigning for all Aboriginal people and to see those campaigners being attacked was an attack on us all. From that time, we became united under one flag.

It was at this time that our cultural survival was hanging by a thread. After years of massacres, slavery and the stolen generations that aimed to assimilate our cultures, the Aboriginal flag became a life raft that helped us find our feet and gave us renewed focus and reaffirmed our identities in a new world that was forced upon us.

From the time images of the flag were broadcast around the nation in 1972 a new symbol of Aboriginal identity was born. By 1977, The City of Newcastle became the first council in Australia to fly the Aboriginal flag. During the 1982 Commonwealth Games in Brisbane, the Aboriginal flag was flying high once again. This time there were dozens of flags, plus there were now flags on t-shirts and badges that were seen on the streets and inside the main QE II stadium. Once again, the media helped spread the news of these actions across Australia.

In 1985, the Aboriginal flag was front and centre of the Uluru handback ceremony and celebrationswhich once again received national and international attention. In 1988, thousands of marchers took to the streets of Sydney to crash Australia’s bicentennial party on January 26. This protest was one of the largest seen in Australia since the Vietnam war and once again the Aboriginal flag was a prominently on display. On the same day on the coast of Dover, England, Burnum Burnum, one of the founders of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy claimed possession of England for all Aboriginal people by striking the Aboriginal flag into the ground on the coast of Dover. Also in 1988, a controversial painting of ‘The first supper’ by Susan Dorothea White caused a stir in Australia. Her painting was based on Leonardo da Vinci’s painting and featured an Aboriginal woman wearing an Aboriginal flag t-shirt in the place of Jesus.

In the 80’s and early 90’s, Peter Garrett, the lead singer of Midnight Oil was often wearing an Aboriginal flag shirt as he performed around Australia at the height of the band’s success. He became one of the first in a long list of celebrities to eventually wear or promote the Aboriginal flag in front of thousands of fans.

In 1994, Cathy Freeman made national headlines when she ran a victory lap after her 400 metres win with the Aboriginal flag at the Commonwealth Games in Canada. She faced heavy criticism for her actions by members of parliament and the head of the Australian Commonwealth Games team Arthur Tunstall. Freeman went on to defy the critics by flying the Aboriginal flag again at the games, at International titles and most famously at the 2000 Sydney Olympics.

In 1997, Hollywood sci-fi film Event Horizon featured Aboriginal flags on the uniform of Hollywood actor Sam Neill. The design appeared to be an Australian flag with the Union Jack replaced by the Aboriginal flag.

In 2000, Redfern’s iconic Aboriginal flag was painted up by former Tongan born world champion kickboxer, Alex Tui at the Block. In the same year we saw 250,000 Indigenous and non-Indigenous people march with the Aboriginal and Australian flags across Sydney Harbour Bridge as part of the Walk for Reconciliation. On May 28th, both flags were also flown together for the first time on top of the Sydney Harbour Bridge on that day. The Aboriginal flag was also flown at Olympic venues during the 2000 Sydney Olympic games.

In 2012, Indigenous boxer, Damien Hooper, wore an Aboriginal flag t-shirt as he stepped into the ring at the London Olympics. Even though the flag was now an official flag of Australia, the Australian Olympic committee demanded Hooper to apologise for his actions to which he refused and declared he was proud of what he did.

In more recent years, other notable celebrities to have showcased the Aboriginal flag on the world stage include Neil Young (2013), Snoop Dog (2012), Common (2014), Jessica Mauboy at Eurovision in 2014, Sprillex (2014), Ed Sheeran (2015) and most recently Roger Waters (2018).

High profile Indigenous sporting stars such as Adam Goodes, Johnathan Thurston, Greg Inglis, Patty Mills have all made sure the Aboriginal flag or the colours of the Aboriginal flag were visible when playing, training or while doing interviews.

In 2017 a petition was started to have the Aboriginal flag flown on top of the Sydney Harbour Bridge for 365 days of the year. After several months the petition received over 80,000 signatures and gained the support of the Labor party in NSW with the current opposition leader Luke Foley making an election promise to fly the Aboriginal flag side by side with the Australian Flag.

With the onset of emojis used on social media, the demands for Aboriginal flag emojis grew louder and louder. In 2017, twitter launched Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flags that appeared whenever Indigenous hashtags were used during Reconciliation Week. Despite calls for Facebook to introduce the Aboriginal flag emojis, the worlds largest social network has failed to do so and has left users to get creative with red, yellow and black heart or circle shaped emojis. In late 2017, Snapchat users were delighted to discover that Aboriginal flag stickers appeared after a regular update. A petition was also started in 2017 calling on Apple to include the Aboriginal flag among the other flags of the world currently present to all users.

In an intriguing move by the government, the Aboriginal flag was granted status as an official flag of Australia on 14 July 1995. This move came under the leadership of former Prime Minister Paul Keating. The move was criticised at the time by the Liberal party who were firmly against it. At the time, opposition leader, John Howard stated that it would be a divisive gesture to make both the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flag. Although the flag was granted this status, the Aboriginal flag continued to unsettle non-Indigenous Australians for years to come as seen in the case of Damian Hooper at the London Olympics and refusals of many local councils to fly the Aboriginal flag.

After the move to grant the flag official status, Harold Thomas was not in favour of the move as he believed the flag had already achieved its purpose of being recognised and accepted by Aboriginal people in Australia. He also felt the government was still not truly aware of the importance and the significance that the Aboriginal flag created for Aboriginal people.

The correct colours of the Aboriginal flag are often not displayed correctly in digital and print media. The correct pantone colours are more dull compared to the bright red and bright yellow that is favoured in digital and print media.

Red: 179C (Pantone) | 204-0-0 (RGB) | #CC0000 (Hex) | 0%–100%–100%–30% (CMYK)

Yellow: 123C (Pantone) | 255–255–0 (RGB) | #FFFF00 (Hex) | 0%–0%–100%–0% (CMYK)

Black: Black C (Pantone) | 0–0–0 (RGB) | #000000 (Hex) | 0%–0%–0%–100% (CMYK)

In 1997, David George Brown, an Aboriginal man from South Australia claimed that he was the designer of the Aboriginal flag. The case went all the way to the Federal Court but there was little hope for Brown who relied on testimonials from old friends from his time in youth detention to back up his story. The court found a number of holes in the story and it ultimately did not stack up with Harold Thomas’s very public activities in 1970 and 1971 at the Museum of South Australia and his close connection and collaboration with Gary Foley.

The fact that a national flag comes under copyright rules has caused a number of frustrations. It’s not so easy to find products or souvenirs that feature the Aboriginal flag as businesses may be unwilling to pay a premium. Luckily, Thomas has no problem with Aboriginal organisations using or incorporating the flag for promotion, however some Aboriginal businesses have expressed concerns about the current arrangement with Birubi Art who Thomas awarded the rights to market and sell Aboriginal flag merchandise. There are serious allegations that Birubi Art is not promoting Aboriginal art in an ethical manner. We hope that these issues can be addressed sooner rather than later. In November 2018 the exclusive flag merchandise agreement was transferred to WAM Clothing which is believed to be owned by the same person behind Birubi Art. Indigenous activists are becoming frustrated with this partnership and there are serious talks underway to design or re-design the Aboriginal flag all together.

Before we mention where to buy an Aboriginal flag, we should mention that it is possible to collect full sized Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander flags for free from local Federal MP offices around Australia. Aboriginal flags can also be purchased online through Amazon. They also stock miniature desk flags too. Both of these products are sold under the Carroll & Richardson – Flagworld name which is the only other business apart from Birubi art that has the right to exclusively sell Aboriginal flag products. Flagworld also offer custom made over sized flags and Aboriginal flag bunting (miniature flags on a rope). All of those items can be purchased via Flagworld’s website.

It is important to remember that as successful as the Aboriginal flag has become at unsettling Australia, the journey is not yet over. The Aboriginal flag owes its fame to the land rights movement and unless we actually see true land rights (not native title), the original fire that made the flag so successful will be at risk of being lost.

Let’s keep the fire burning!