The “war to end all wars” was over, but a new one was just beginning—on the streets of America.

It wasn’t much of a fight, really—at least at the start.

On the one side was a rising tide of professional criminals, made richer and bolder by Prohibition, which had turned the nation “dry” in 1920. In one big city alone— Chicago—an estimated 1,300 gangs had spread like a deadly virus by the mid-1920s. There was no easy cure. With wallets bursting from bootlegging profits, gangs outfitted themselves with “Tommy” guns and operated with impunity by paying off politicians and police alike. Rival gangs led by the powerful Al “Scarface” Capone and the hot-headed George “Bugs” Moran turned the city streets into a virtual war zone with their gangland clashes. By 1926, more than 12,000 murders were taking place every year across America.

On the other side was law enforcement, which was outgunned (literally) and ill-prepared at this point in history to take on the surging national crime wave. Dealing with the bootlegging and speakeasies was challenging enough, but the “Roaring Twenties” also saw bank robbery, kidnapping, auto theft, gambling, and drug trafficking become increasingly common crimes. More often than not, local police forces were hobbled by the lack of modern tools and training. And their jurisdictions stopped abruptly at their borders.

In the young Bureau of Investigation, things were not much better. In the early twenties, the agency was no model of efficiency. It had a growing reputation for politicized investigations. In 1923, in the midst of the Teapot Dome scandal that rocked the Harding Administration, the nation learned that Department of Justice officials had sent Bureau agents to spy on members of Congress who had opposed its policies. Not long after the news of these secret activities broke, President Calvin Coolidge fired Harding’s Attorney General Harry Daugherty, naming Harlan Fiske Stone as his successor in 1924.

Kingpins like Al Capone were able to rake in up to $100 million each year thanks to the overwhelming business opportunity of illegal booze.

The term “organized crime” didn’t really exist in the United States before Prohibition. Criminal gangs had run amok in American cities since the late 19th-century, but they were mostly bands of street thugs running small-time extortion and loansharking rackets in predominantly ethnic Italian, Jewish, Irish and Polish neighborhoods.

In fact, before the passing of the 18th Amendment in 1919 and the nationwide ban that went into effect in January 1920 on the sale or importation of “intoxicating liquor," it wasn’t the mobsters who ran the most organized criminal schemes in America, but corrupt political “bosses,” explains Howard Abadinsky, a criminal justice professor at St. John’s University and author of Organized Crime.

More than any other author, F. Scott Fitzgerald can be said to have captured the rollicking, tumultuous decade known as the Roaring Twenties, from its wild parties, dancing and illegal drinking to its post-war prosperity and its new freedoms for women.

Above all, Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel The Great Gatsby has been hailed as the quintessential portrait of Jazz Age America, inspiring Hollywood adaptations populated by dashing bootleggers and glamorous flappers in short, fringed dresses.

But amid that decade of newfound prosperity and economic growth, Fitzgerald—like other writers of the so-called “Lost Generation”—wondered if America had lost its moral compass in the rush to embrace post-war materialism and consumer culture. While The Great Gatsby captures the exuberance of the 1920s, it’s ultimately a portrayal of the darker side of the era, and a pointed criticism of the corruption and immorality lurking beneath the glitz and glamour.

The 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted American women the right to vote, a right known as women’s suffrage, and was ratified on August 18, 1920, ending almost a century of protest. In 1848, the movement for women’s rights launched on a national level with the Seneca Falls Convention, organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott.

Following the convention, the demand for the vote became a centerpiece of the women’s rights movement. Stanton and Mott, along with Susan B. Anthony and other activists, raised public awareness and lobbied the government to grant voting rights to women. After a lengthy battle, these groups finally emerged victorious with the passage of the 19th Amendment.

Despite the passage of the amendment and the decades-long contributions of Black women to achieve suffrage, poll taxes, local laws and other restrictions continued to block women of color from voting. Black men and women also faced intimidation and often violent opposition at the polls or when attempting to register to vote. It would take more than 40 years for all women to achieve voting equality.

OVERVIEW

As the 1920s began, the world was uplifted by the end of World War I (1914–1918) and the anticipation of a peaceful era. New inventions, a booming economy, a soaring stock market, upbeat music, and a rise in international trade and banking led to a feeling of buoyancy and optimism, as well as new jobs and opportunities for people to become prosperous.

For the first time, many working-class families could afford to buy automobiles, and American society as a whole became more mobile. Henry Ford’s (1863–1947) Model T was the most basic automobile, but as the decade went on other manufacturers began introducing a great variety of other vehicles, some more luxurious than Ford’s. In addition, advertisers began using more...

The Roaring Twenties was a period in American history of dramatic social, economic and political change. For the first time, more Americans lived in cities than on farms. The nation’s total wealth more than doubled between 1920 and 1929, and gross national product (GNP) expanded by 40 percent from 1922 to 1929. This economic engine swept many Americans into an affluent “consumer culture” in which people nationwide saw the same advertisements, bought the same goods, listened to the same music and did the same dances. Many Americans, however, were uncomfortable with this racy urban lifestyle, and the decade of Prohibition brought more conflict than celebration. But for some, the Jazz Age of the 1920s roared loud and long, until the excesses of the Roaring Twenties came crashing down as the economy tanked at the decade’s end.

With unprecedented prosperity, technology, and leisure like no decade before it, 1920s America roared, soared, and was never bored, igniting endless fads and crazes of excess and frivolity–until it all came crashing down.

The decade before survived the cataclysm of World War I and a deadly global influenza epidemic. This brought about a cynical post-war mindset: “Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow you may die.” At the same time, long-simmering efforts like the temperance movement rose to the surface that led to high-minded laws that brought about unforeseen consequences and made law breakers out of the everyday citizen. When the decade ended in 1929 with the crash of the stock market, Americans were left wondering what had happened.

POSTWAR REACTION

When the decade of the 1920s began, Americans were anxious to forget the world war they had recently fought and eager to roll back the clock to an era of innocence, a time that doubtless never existed. The reluctance of the Senate to ratify the Treaty of Versailles—which officially ended the war with Germany and established the terms of the peace that followed—loomed large in the early months of the new decade. Reflecting popular opinion the Senate resisted President Woodrow Wilson's proposed League of Nations. Isolationist sentiment also prevailed in the Senate debate over the ratification of the treaty, revealing Americans' unwillingness to accept the responsibilities of world leadership. Americans sought to keep the world at bay, clamoring for immigration restrictions to protect their culture against the perceived threat of foreign radicals, to reduce economic competition from immigrant workers, and to prevent a general bombardment of the United States with heterogeneous religious beliefs and cultural values.

The technological advances of the beginning of the century continued to impact lives in the 1920s. Henry Ford (1863–1947) had improved his assembly-line techniques to produce a Model T every ten seconds by 1925. Automobiles were more affordable than ever: Some models sold for as little as $50. By the end of the decade, 23.1 million passenger cars crowded the streets of America. Telephones were in 13 percent of American homes by 1921, and American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T) had become America's largest corporation by 1925.

. Courtesy of New York Public Library

Courtesy of New York Public Library

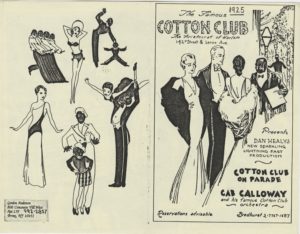

This 1927 program for the Cotton Club, New York’s foremost nightclub and speakeasy during Prohibition and many years beyond it, advertised Cab Calloway and his orchestra. The program shows that the club, featuring African-American performers, catered to a wealthy white crowd.

When Prohibition took effect on January 17, 1920, many thousands of formerly legal saloons across the country catering only to men closed down. People wanting to drink had to buy liquor from licensed druggists for “medicinal” purposes, clergymen for “religious” reasons or illegal sellers known as bootleggers. Another option was to enter private, unlicensed barrooms, nicknamed “speakeasies” for how low you had to speak the “password” to gain entry so as not to be overheard by law enforcement.

During Prohibition, gay nightlife and culture reached new heights—at least temporarily.

On a Friday night in February 1926, a crowd of some 1,500 packed the Renaissance Casino in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood for the 58th masquerade and civil ball of Hamilton Lodge.

Nearly half of those attending the event, reported the New York Age, appeared to be “men of the class generally known as ‘fairies,’ and many Bohemians from the Greenwich Village section who...in their gorgeous evening gowns, wigs and powdered faces were hard to distinguish from many of the women.”

The tradition of masquerade and civil balls, more commonly known as drag balls, had begun back in 1869 within Hamilton Lodge, a black fraternal organization in Harlem. By the mid-1920s, at the height of the Prohibition era, they were attracting as many as 7,000 people of various races and social classes—gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and straight alike.

Stonewall (1969) is often considered the beginning of forward progress in the gay rights movement. But more than 50 years earlier, Harlem’s famous drag balls were part of a flourishing, highly visible LGBTQ nightlife and culture that would be integrated into mainstream American life in a way that became unthinkable in later decades.

The Prohibition Era began in 1920 when the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which banned the manufacture, transportation and sale of intoxicating liquors, went into effect with the passage of the Volstead Act. Despite the new legislation, Prohibition was difficult to enforce. The increase of the illegal production and sale of liquor (known as “bootlegging”), the proliferation of speakeasies (illegal drinking spots) and the accompanying rise in gang violence and organized crime led to waning support for Prohibition by the end of the 1920s. In early 1933, Congress adopted a resolution proposing a 21st Amendment to the Constitution that would repeal the 18th. The 21st Amendment was ratified on December 5, 1933, ending Prohibition.

BACKGROUND

Americans had consumed alcohol since colonial times. Like Europeans, American colonists generally considered alcoholic beverages safer to drink than potentially polluted water, and weak beer and cider were consumed by adults and children alike on a daily basis. Public drunkenness, however, was socially unacceptable.

By the 1700s, drinking habits changed as rum, imported from the Caribbean and distilled locally, became widely available. In the 1760s, a new kind of liquor, whiskey, also appealed to colonists. As these potent alcoholic drinks gained popularity, social norms surrounding alcohol consumption and public drunkenness relaxed. Excessive rum and whiskey consumption by the colonists attracted negative attention from religious and political leaders alike as early as the mid-1700s. By the late 1700s, the many negative effects from overuse of “ardent spirits” (as distilled liquors were commonly called) were the subjects of medical treatises and religious tracts. In 1784 Benjamin Rush (1746–1813), a doctor and one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, published An Inquiry into the Effects of Ardent Spirits Upon the Human Body and Mind, a pamphlet that detailed the negative health consequences of alcohol abuse, positing a model of physical addiction similar to that supported by physicians in modern times. Church leaders, meanwhile, focused on the negative social effects of alcohol abuse, including loss of livelihood and increased domestic violence.

In August 1929, Ladies Home Journal published an article titled “Everybody Ought to Be Rich.” In it, businessman John J. Raskob told Americans that if they invested $15 in the stock market every month, in 20 years they could have $80,000 (over $1 million today). Raskob insisted that “almost anyone who is employed can do that if he tries.”

For wealthy, white Americans like Raskob, the “Roaring ‘20s” was a time of immense economic prosperity. Yet for most Americans, it wasn’t. Low-wage jobs paid an average of $25 a week for men and $18 for women. So if low-wage workers had followed Raskob’s advice, they would have been placing most of a week's earnings in the stock market every month.

In fact, income inequality increased so much during the 1920s, that by 1928, the top one percent of families received 23.9 percent of all pretax income. About 60 percent of families made less than $2,000 a year, the income level the Bureau of Labor Statistics classified as the minimum livable income for a family of five.

As Americans dreamed of amassing fabulous fortunes, many became vulnerable to cons.

The economy boomed during the Roaring Twenties and rising incomes gave ordinary Americans access to enticing new conveniences, including washing machines, refrigerators, cars and other luxuries that would have once seemed unattainable.

But for many, that wasn’t enough.

With newly-minted Wall Street millionaires flaunting their mansions and opulent lifestyles in a style akin to the protagonist of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel The Great Gatsby, it was easy for an average Joe to dream big and envision parlaying a few dollars in hard-earned savings into a similarly vast fortune.

That eagerness played right into the hands of the Roaring Twenties’ legions of fast-talking promoters, charlatans and outright swindlers, who enticed the would-be wealthy with scores of seemingly foolproof schemes—from stock in companies that didn’t really exist, to speculation in Florida real estate or California oilfields, to Boston-based conman Charles Ponzi’s promise that investors could make a 50 percent return in 90 days’ time by investing in a bizarre plan to redeem overseas postal coupons.

Were financial institutions victims—or culprits?

On the surface, everything was hunky-dory in the summer of 1929. The total wealth of the United States had almost doubled during the Roaring Twenties, fueled, in part, by stock market speculation eagerly undertaken by a wide swath of citizens ranging from Fifth Avenue dowagers to factory workers. One Midwestern woman, a farmer, made an overnight profit of $2,000 ($31,000 in today’s dollars) betting on a car manufacturer’s stock.

When the bubble burst in spectacular fashion in October 1929, many economists, including John Kenneth Galbraith, author of The Great Crash 1929, blamed the worldwide, decade-long Great Depression that followed on all those reckless speculators. Most saw the banks as victims, not culprits.

By 1929, a perfect storm of unlucky factors led to the start of the worst economic downturn in U.S. history.

The Great Depression, a worldwide economic collapse that began in 1929 and lasted roughly a decade, was a disaster that touched the lives of millions of Americans—from investors who saw their fortunes vanish overnight, to factory workers and clerks who found themselves unemployed and desperate for a way to feed their families.

Some people were reduced to selling apples on street corners to support themselves, while others lost their homes and were forced to survive in shanty towns that became known as “Hoovervilles,” a bitterly derisive reference to President Herbert Hoover, who in the early 1930s often claimed that “prosperity was just around the corner,” even as economic and trade policy mistakes and reluctance to provide government assistance to ordinary Americans worsened their predicament.

The Stock Market Crash of 1929 occurred on October 29, 1929, when Wall Street investors traded some 16 million shares on the New York Stock Exchange in a single day. Billions of dollars were lost, wiping out thousands of investors. In the aftermath of that event, sometimes called “Black Tuesday,” America and the rest of the industrialized world spiraled downward into the Great Depression, the deepest and longest-lasting economic downturn in the history of the Western industrialized world up to that time.

Jazz had spread to dance halls and other venues, including speakeasies, all over America by the mid nineteen-twenties. Early jazz influences started to manifest themselves in the music used by marching bands and dance bands of the day, which was the main form of popular concert music in the early twentieth century.

1920s music was called, "a combination of nervousness, lawlessness, primitive savage animalism, and lasciviousness."

A group of 1920's Musicians with their instruments

Jazz was the music of the 1920's: loud and syncopated. This was the Jazz Age!

The jazz recordings were often called "race records," and were sold and played typically in the black neighborhoods of large cities like New York and Chicago.

Controversial throughout its history, jazz was America's first contribution to the music world. And it all got started in the 1920's.

Manhattan is the jewel of New York with Broadway at its center.

Early settlers of the island of Manhattan were amazed by the amount and the diversity of the wildlife and the beauty of the forest. Lobsters as long as a man's arm were stacked upon the ocean floor, and fish jumped freely into canoes.

Obviously the natural diversity is gone these days, yet diversity remains in the people who walk the streets of New York. Broadway blossomed and began showing the true colors of what it would come to be in the the later half of the 20th century.

From Sunset Boulevard to Grauman's Chinese Theater, Hollywood in the 1920s was a vintage spectacle not to be missed.

From the beautiful and handsome leading ladies and gentlemen, Hollywood was an ever widening hub of celebrity, debauchery and decadence in the Roaring Twenties.

It was both a town of wealth and glamor and a seedy place where brothels posed as fake acting schools and sucked in attractive young girls who traveled to California with dreams of stardom and fortune in their eyes.

The Golden Age of Hollywood was a period of great growth, experimentation and change in the industry that brought international prestige to Hollywood and its movie stars.

Under the all-controlling studio system of the era, five movie studios known as the “Big Five” dominated: Warner Brothers, RKO, Fox, MGM and Paramount. Smaller studios included Columbia, Universal and United Artists.

The Golden Age of Hollywood began with the silent movie era (though some people say it started at the end of the silent movie age). Dramatic films such as D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915) and comedies such as The Kid (1921) starring Charlie Chaplin were popular nationwide. Soon, movie stars such as Chaplin, the Marx Brothers and Tallulah Bankhead were adored everywhere.

With the introduction of movies with sound, Hollywood producers churned out Westerns, musicals, romantic dramas, horror films and documentaries. Studio movie stars were even more idolized, and Hollywood increased its reputation as the land of affluence and fame.

During World War I, after President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany, the Big Five jumped on the political propaganda bandwagon.

Often under pressure and guidance from the Wilson administration, they produced educational shorts and reels on war preparedness and military recruitment. They also lent out their wide roster of popular actors to promote America’s war efforts.

By the 1930s, at the height of Hollywood’s Golden Age, the movie industry was one of the largest businesses in the United States. Even in the depths of the Great Depression, movies were a weekly escape for many people who loved trading their struggles for a fictional, often dazzling world, if only for a couple of hours.

Despite the tough economic times, it’s estimated up to 80 million Americans went to the movies each week during the Depression.

Some of the greatest films made in all of Hollywood history were made in the late 1930s, such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Gone with the Wind, Jezebel, A Star Is Born, Citizen Kane, The Wizard of Oz, Stagecoach and Wuthering Heights.